It is often said that the only way to reduce migration to Europe, North America and other wealthy countries is to stimulate development in poor countries.

This sounds very logical. But it is a myth. In reality, social and economic development in poor countries leads to more migration. If you don't believe it, please look at this graph:

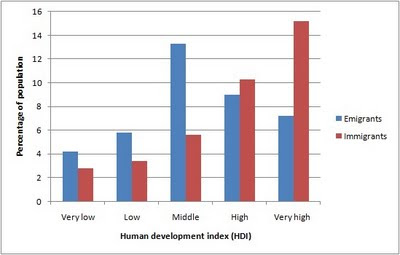

This graph (from this recent study) ranks all countries in the world according to the level of human development. This is an index used by the United Nations Development Programme to measure the level of development of countries, and is calculated on the basis of three indicators: life expectancy at birth, years of schooling and income (GNI) per head of the population. It is a rough indicator of the quality of life and living standards in countries.

I divided all countries of the world countries in five, equally large groups ranging from very low to very high levels of human development. The blue and red bars indicate the number of emigrants (citizens living abroad) and immigrants (people born abroad) as a percentage of the total population (using 2000 data). It shows a striking pattern

It is therefore no coincidence that the most important emigration countries in the world, such as Mexico, Morocco, Turkey and the Philippines are not the poorest countries in the world.

But it's not only money that matters. Also education and access to modern media such as satellite television and Internet plays explain why development initially leads to more migration. If people go to school, they increase their life aspirations, become more aware of opportunities elsewhere. Together with schooling, also access to modern media lead to people aspire better opportunities and different lifestyles.

When I lived in a Moroccan oasis for my research, my young friends, who were all peasants' sons and had gone to school, simply could not imagine a future on the farm anymore. Again, this was not only related to the lack of jobs on the countryside; they found life on the countryside simply "boring". They wanted to go and live in Casablanca or Marrakesh, or to go to Europe.

These processes are universal. It reminded me of my own mother, who also could not image a life on the farm anymore in the far north of the Netherlands, and went to Amsterdam. My parents moved back to Frisia in the north when they founded a family, until it was my turn to get bored and so I moved "back" to Amsterdam at the age of 18.

It is an illusion that you can stop this. Most young people, particularly when they are educated, want to explore the world and discover new horizons. European and American students find it perfectly normal to take a "gap year" to travel around the world, but are surprised when young Africans or Asians show the same sense of adventure and want to discover the world. The tendency is to portray them as "desperate" and "poor" whereas the majority of migrants from developing countries are better off than those who are forced to stay behind.

Several studies about past migration have shown the same pattern. For instance, in the 19th century, most immigrants in the United States came from Britain and other North Sea countries, while migration from poorer, less developed countries in southern and eastern Europe, which were lagging behind in industrial development and urbanization, took off much later.

What can we conclude from this? If countries such as Morocco and Mexico will experience rapid growth and economic development, we can experience a decline in emigration from those countries and an increase in immigration. In recent decades, such 'migration transitions" have also happened with countries such as Spain, Italy, Greece, Ireland, South Korea, Taiwan; and Turkey seems in the middle of such a transition.

But development in the least developed countries, many of which are located in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, will almost inevitably lead to take-off emigration from those countries.

Therefore, future immigrants in Europe might increasingly come from sub-Saharan African instead of North African countries.

The graph and the study on which it is based also show something more fundamental: the need to see migration as an intrinsic - and therefore inevitable - part of human development rather than a problem to be solved.

This sounds very logical. But it is a myth. In reality, social and economic development in poor countries leads to more migration. If you don't believe it, please look at this graph:

|

| (c) Hein de Haas |

I divided all countries of the world countries in five, equally large groups ranging from very low to very high levels of human development. The blue and red bars indicate the number of emigrants (citizens living abroad) and immigrants (people born abroad) as a percentage of the total population (using 2000 data). It shows a striking pattern

- Immigration goes steadily up with the levels of development. More developed countries are more attractive. This makes sense. It also indicates that highly developed countries are inevitably high immigration societies.

- The surprise is in the blue bars: emigration initially goes up with levels of development, and only goes down once countries move into high development categories. It indicates that if poor countries become wealthier, emigration will increase.

It is therefore no coincidence that the most important emigration countries in the world, such as Mexico, Morocco, Turkey and the Philippines are not the poorest countries in the world.

But it's not only money that matters. Also education and access to modern media such as satellite television and Internet plays explain why development initially leads to more migration. If people go to school, they increase their life aspirations, become more aware of opportunities elsewhere. Together with schooling, also access to modern media lead to people aspire better opportunities and different lifestyles.

When I lived in a Moroccan oasis for my research, my young friends, who were all peasants' sons and had gone to school, simply could not imagine a future on the farm anymore. Again, this was not only related to the lack of jobs on the countryside; they found life on the countryside simply "boring". They wanted to go and live in Casablanca or Marrakesh, or to go to Europe.

These processes are universal. It reminded me of my own mother, who also could not image a life on the farm anymore in the far north of the Netherlands, and went to Amsterdam. My parents moved back to Frisia in the north when they founded a family, until it was my turn to get bored and so I moved "back" to Amsterdam at the age of 18.

It is an illusion that you can stop this. Most young people, particularly when they are educated, want to explore the world and discover new horizons. European and American students find it perfectly normal to take a "gap year" to travel around the world, but are surprised when young Africans or Asians show the same sense of adventure and want to discover the world. The tendency is to portray them as "desperate" and "poor" whereas the majority of migrants from developing countries are better off than those who are forced to stay behind.

Several studies about past migration have shown the same pattern. For instance, in the 19th century, most immigrants in the United States came from Britain and other North Sea countries, while migration from poorer, less developed countries in southern and eastern Europe, which were lagging behind in industrial development and urbanization, took off much later.

What can we conclude from this? If countries such as Morocco and Mexico will experience rapid growth and economic development, we can experience a decline in emigration from those countries and an increase in immigration. In recent decades, such 'migration transitions" have also happened with countries such as Spain, Italy, Greece, Ireland, South Korea, Taiwan; and Turkey seems in the middle of such a transition.

But development in the least developed countries, many of which are located in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, will almost inevitably lead to take-off emigration from those countries.

Therefore, future immigrants in Europe might increasingly come from sub-Saharan African instead of North African countries.

The graph and the study on which it is based also show something more fundamental: the need to see migration as an intrinsic - and therefore inevitable - part of human development rather than a problem to be solved.